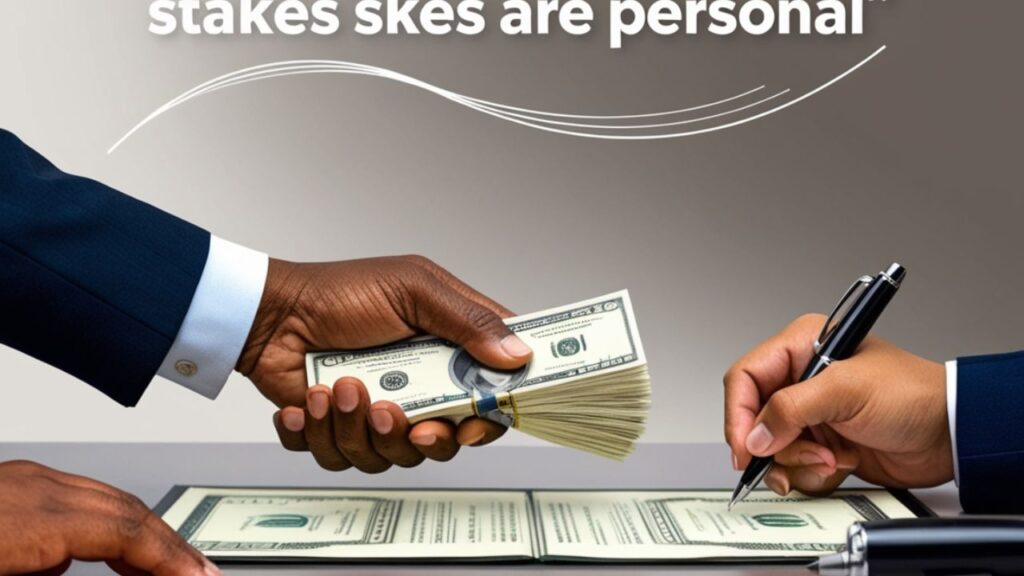

Skin in the Game means putting your own money, time, or reputation at risk. It shows you care about the outcome and want to be responsible. Leaders and founders use it to prove commitment and build trust with others.

The origin of skin in the game comes from old gambling and business practices. People who risked their own cash or resources were trusted more. Over time, it became a rule in finance and leadership to show accountability.

Real examples of skin in the game include founders investing personal savings in startups. CEOs tying salaries to company performance also show alignment. Even non-profits ask board members to give time or money to prove dedication.

What Does “Skin in the Game” Actually Mean?

Skin in the Game means putting your own money, time, or reputation at risk to show responsibility. People notice when someone has personal stake in a project, which builds trust and encourages better decisions.

When someone has skin in the game, their interests match the outcomes. Leaders, investors, and founders act carefully because failure affects them too. This creates accountability, strengthens credibility, and shows others they are serious about their commitments.

Key principles:

- Risk-sharing – You put something valuable on the line.

- Accountability – You face real consequences for your actions.

- Alignment – Your interests match the outcomes of the project.

- Trust-building – Others see your commitment and reliability.

- Decision quality – Personal stakes encourage careful, responsible choices.

Origin and Etymology: Where Did “Skin in the Game” Come From?

The phrase Skin in the Game started in early 20th-century gambling. Players who risked their own money earned more trust. This idea later spread to business and finance, showing personal commitment matters in serious decisions.

Over time, skin in the game became common in Wall Street and corporate circles. Executives and investors used it to show accountability. People trusted those who had real stakes in outcomes, linking responsibility directly to personal risk.

Famous leaders like Warren Buffett popularized the term in investment settings. He required executives to hold company shares to prove confidence. This practice reinforced credibility and showed that risk alignment strengthens trust between leaders and stakeholders.

Philosopher Nassim Nicholas Taleb expanded the meaning further. He emphasized moral and systemic integrity, showing that true skin in the game ensures ethical decisions and shared responsibility. The term evolved from casual slang to essential business wisdom.

See also : Minuet vs Minute: Grammar, Usage & Pronunciation Tips

Literal vs. Figurative Meaning: Understanding the Dual Layers

The literal meaning of Skin in the Game involves risking personal money. Gamblers and investors showed honesty by using their own cash. This physical risk ensured responsibility and built trust in financial and business settings.

Figuratively, skin in the game includes reputation, career, and strategic risks. Leaders and founders take personal stakes to show commitment. This strengthens credibility, encourages accountability, and ensures people act carefully when their own outcomes are on the line.

Figuratively, it now encompasses:

- Financial risk – cash, equity, or capital held personally.

- Reputational risk – stakes in credibility, integrity, and trust.

- Strategic risk – personal career capital tied to outcomes.

Let’s illustrate :

| Type of Skin | Definition | Example |

| Financial | Personal money at risk | Founder investing $1M of own capital into startup |

| Reputational | Public and professional reputation risk | Analyst publicly backing a stock, then proven wrong |

| Strategic | Future opportunities or career at stake | CEO tying stock options to company performance |

Both layers matter. Financial skin shows you believe in something. Figurative skin ensures you feel consequences if things go wrong.

Who Made It Famous? Thought Leaders Behind the Term

Leaders like Warren Buffett and Nassim Nicholas Taleb made Skin in the Game popular. They showed that personal stakes build trust, credibility, and accountability. Executives and investors following their ideas prove commitment and act responsibly in business and finance.

Warren Buffett

Warren Buffett requires executives to invest their own money in the companies they lead. This practice shows real commitment and aligns leaders’ decisions with shareholders’ interests, building strong trust in business and finance.

Buffett believes that when leaders have personal stakes, they act responsibly and avoid reckless choices. His approach demonstrates that skin in the game strengthens accountability, credibility, and long-term success for both executives and investors.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Nassim Nicholas Taleb emphasized that true skin in the game ensures fairness and moral responsibility. People making decisions feel consequences, which prevents careless or unethical behavior. This idea applies to business, finance, and daily life.

Taleb warned against leaders and experts who avoid personal risk. Without stakes, their choices can harm others. Accountability comes from having something real on the line, creating alignment between actions and outcomes.

His work shows that credibility and trust grow when decision-makers share risks. By linking personal stakes to results, Taleb highlights that skin in the game strengthens ethics, responsibility, and confidence in leadership and investments.

Joseph Stiglitz

Joseph Stiglitz highlighted that lack of skin in the game caused major problems in the 2008 financial crisis. Bankers and executives took risks without personal stakes, which increased reckless behavior and harmed the economy.

Stiglitz argues that personal investment by leaders improves accountability. When decision-makers face real consequences, they act more carefully and responsibly. This alignment of interests reduces moral hazard and encourages ethical behavior in finance and business.

He also shows that credibility grows when leaders share risks with stakeholders. Executives who put their own money or reputation on the line inspire trust, proving that true commitment strengthens long-term success and decision-making outcomes.

See also : Staccato Sentences Explained: Usage, Tips & Examples

How “Skin in the Game” Shapes Business and Finance

In modern enterprises, aligning incentives between stakeholders is critical. Skin in the game creates :

- Better decision-making – Leaders avoid reckless risks.

- Increased trust – Stakeholders see their interests reflected.

- Stronger oversight – Investors and employees know leaders can’t walk away.

Examples: - Startup founders often invest personal savings or property.

- Senior executives tie salaries to stock performance.

- Venture funds co-invest with limited partners to show alignment.

- Statistics confirm this: companies with high insider ownership outperformed peers by 2.3% annually

over the last decade (Source: Institutional Investor data). That’s not fluff – that’s earned credibility.

Aligning Executive and Shareholder Interests

Aligning executive and shareholder interests ensures leaders share risks and rewards with investors. Using stock options, equity stakes, or long-term incentives builds accountability and trust, showing that executives’ actions directly support company performance and stakeholder confidence.

Aligning interests is both an art and strategy. Common vehicles include:

- Equity-based compensation: Stock options and RSUs tie management’s gains to company performance.

- Golden handcuffs: Vesting schedules encourage long-term engagement.

- Ownership requirements: Boards often require senior leaders to hold a set percentage of shares.

These aren’t window-dressing – they carry real impact. A 2023 Harvard Business Review analysis found that CEO stock ownership over 5% correlated with a 15% lower risk of unethical behavior and 7% higher employee satisfaction.

What the SEC Requires: Disclosures, Transparency, and Accountability

The SEC requires executives to disclose their ownership and trades. Forms like Form 3, Form 4, and Form 5 ensure transparency, letting investors see who has real skin in the game and how leaders’ actions align with company interests.

These disclosures improve accountability and prevent misuse of information. When leaders report stock purchases or sales, stakeholders gain trust, knowing executives face real consequences for their financial and reputational decisions, which strengthens overall confidence in business practices.

Aligning interests is both an art and strategy. Common vehicles include:

- Equity-based compensation: Stock options and RSUs tie management’s gains to company performance.

- Golden handcuffs: Vesting schedules encourage long-term engagement.

- Ownership requirements: Boards often require senior leaders to hold a set percentage of shares.

The Limits of “Skin in the Game”: Where the System Breaks

Even with skin in the game, problems can happen. Executives may hide stakes, front-run trades, or invest through secret accounts. These actions reduce accountability and mislead others, showing that personal risk alone cannot guarantee complete credibility.

Overexposure also creates risks. Leaders who commit too much money or reputation may act emotionally or make poor choices. Proper balance ensures alignment and responsibility while avoiding negative consequences for themselves and stakeholders.

Skin in the game isn’t always foolproof. It presents risk:

- Front-running: Executives buying ahead of announcements.

- Commingled funds: Leaders invest in mutual funds that hide real stakes.

- Shadow investing: Using shell accounts to mask ownership.

Case example: The 2011 SAC Capital insider trading scandal involved executives exercising stock options ahead of major news – revealed after an SEC investigation.

Solution? Transparency – clear, verifiable, and aligned with shareholders.

Does “Skin in the Game” Signal Trust or Is It Just Theater?

Skin in the game often builds trust, but sometimes it is just theater. Token investments, small stakes, or PR-driven actions may appear meaningful but lack real accountability or commitment.

True trust comes from visible, verifiable stakes. Leaders and investors who genuinely share risk strengthen credibility, showing others that their decisions carry real consequences and reflect sincere commitment .

Often, insider ownership builds confidence. But it’s not always meaningful.

Theater signals are deceptive :

- Token ownership – very small holdings.

- Deferred compensation – promises not actual risk.

- Front-loaded narrative – buying shares for PR without genuine belief.

Psychological insights:

- Overconfidence bias – bullish executives may overstate their stakes.

- Ingroup favoritism – leadership insiders may signal alignment for social validation, not ethics.

So, while skin in the game is often credible, you must dig deeper to see whether it’s real or staged.

Real-World Examples Across Industries

Real-world examples across industries show skin in the game clearly. Elon Musk invested personal money in Tesla, Airbnb founders used their own funds, and nonprofit leaders contribute time or resources, demonstrating commitment, trust, and accountability in every sector.

Elon Musk’s Investment in Tesla

- Musk invested $70 million personally in 2008 during a liquidity crisis.

- Currently holds ~13% of Tesla shares (Source: SEC filings Q1 2025).

- That personal stake aligns his performance directly with shareholders.

Venture Capital and Founders

- Founders often invest personal equity and sweat equity.

- Case: Airbnb’s founders invested ~$500,000 in early rounds while raising $30 million externally – showing commitment and boosting investor confidence.

Politics and Economic Policy

- Examples include politicians investing in industries they regulate.

- Controversial ties: Lobbyists funding campaigns while executives serve in office – a direct conflict of interest.

Nonprofit Sector

- Board members investing personal time or money in causes they lead.

- Example: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation requiring trustees to allocate annual personal donations.

The Principal-Agent Problem and “Skin in the Game”

The principal-agent problem happens when leaders act for owners but lack personal stakes. Skin in the game solves this by making executives share risks, improving accountability, reducing misaligned behavior, and ensuring decisions reflect both personal and company interests.

The principal-agent problem arises when decision-makers (agents) act for owners (principals) but lack aligned incentives. Skin in the game mitigates it:

- Agents bear risk, making them more responsible.

- Reduces misaligned behavior like profit grabbing or intentional short-termism.

- Improves governance – boards see real commitment.

Case study: 2015 turnaround at GE showed strong leadership equity holdings triggered three straight years of improved profitability and cultural shift.

How to Demonstrate “Skin in the Game” in the Real World

To show skin in the game, leaders and founders invest personal money, time, or reputation. Public disclosures, contracts, and equity stakes prove commitment, while following through on promises strengthens trust and signals real accountability in business and finance.

If you want to broadcast your commitment:

- State it directly: “I’ve invested $X of my own money.”

- Show the contract: e.g., vesting schedules, equity stakes.

- Use non-financial skin: your personal reputation, career, or time investment.

- Highlight public disclosures: SEC filings, personal financial reports.

- Match actions with talk: follow through with ownership or effort.

In sales pitches or partnership talks, this builds trust sincerely and effectively.

When “Skin in the Game” Goes Wrong: Risks and Repercussions

Skin in the game can backfire if leaders overcommit money, time, or reputation. Overexposure creates bias, poor decisions, or legal issues. Proper alignment and measured stakes maintain accountability while avoiding negative consequences for executives and stakeholders.

Overexposure can be dangerous:

Legal backlash – especially when insider trading lines get crossed.

Emotional bias – inability to pivot due to ego on the line.

Concentration risk – financial or reputational overcommitment.

Example: A CEO owning 90% of a company might struggle to make objective exit decisions – bias clouds judgment.

Popular Culture References and Media Mentions

Skin in the game appears in books, documentaries, and media quotes. References in works like Taleb’s Skin in the Game and Ray Dalio’s Principles highlight its importance, showing credibility and commitment matter in everyday business and leadership.

The term features in both serious and lighthearted media:

- Books: Principles by Ray Dalio and Skin in the Game by Taleb reference it heavily.

- Documentaries: Inside Job (2010) highlighted lack of skin among bankers.

- Media quotes: “If you talk the talk, you better walk the walk”

- Anonymous VC

- Memes: Social media often depicts “No skin in the game, no empathy.”

These cultural references reinforce its importance in everyday perception.

Final Thoughts

When leaders and decision-makers put their own money, time, or reputation at risk, it shows real commitment. Skin in the game builds trust, strengthens accountability, and ensures actions align with both personal and organizational goals.

This principle applies across business, finance, and nonprofit work. Genuine stakeholding demonstrates responsibility and credibility, encouraging better decisions. Leaders who embrace skin in the game inspire confidence, proving that real involvement matters more than words or promises.

FAQs

What qualifies as “skin in the game”?

It includes personal stakes in money, reputation, time, or career. Any risk that aligns your interests with outcomes counts as skin in the game.

Is it always financial?

No, skin in the game can involve reputational risk, strategic commitments, or time investment. Financial risk is common but not the only form.

Can someone fake it?

Yes, superficial ownership, token investments, or PR-driven actions can simulate commitment. True skin in the game requires verifiable, meaningful personal stakes.

How much skin is enough?

Enough to create real consequences for failure. Minimal token stakes often fail; genuine skin in the game aligns incentives and accountability effectively.

Is it always a good thing?

Not always. Overexposure, emotional bias, or concentration risk can harm decisions. Proper balance ensures benefits without negative repercussions.

Join Bibcia on a journey to master English grammar. Discover easy lessons, writing tips, and practical examples designed to make learning grammar simple and effective.